This time I had cleverly remembered that as after the procedure it is impossible to wear my relatively tight jeans I needed to pack some soft leggings. Last time, once on the ward under observation, Sophie, who was my assistant number one for that trip, went in search of some cheap leggings so that I would have something to wear when it came to leaving the hospital. She returned with possibly the most ugly blue leggings with plastic dark blue stars splattered over them and elasticated bottoms. It would have been hard to have found anything more unattractive if I had paid her. But I had no choice, knowing that public exposure would be minimal between the hospital, the taxi and the hotel, especially as it was dark by the time we got back to our room. The next day my leg was not better and it was clear that I would have to wear this monstrosity of a piece of clothing to the airport and on the plane. When I arrived home I was very tired.

Rupert had run me a bath and Ella made me my juice. Rupert chatted as I undressed and heaved my leg over the side of the bath ready for a good soak. I looked down and honestly my heart almost stopped. My legs were blue. Panic just welled up - the operation must have gone wrong, maybe the artery was blocked (my biology was never very good). As Rupert updated me on family and work I feigned total calm surreptitiously grabbing my phone which was on a stool nearby and started googling ‘symptom checker, blue legs’. The following medical conditions are some of the possible causes of leg blueness. Vascular insufficiency; coagulopathy; haematoma; peripheral vascular disease; arterial embolus… Or A bluish tinge to the skin is known as cyanosis. It is a very serious sign of low oxygen levels and build up of carbon dioxide’

I felt tired but I didn't feel that bad. My heart just started pumping and pumping and I felt light headed with shock. What was panicking me was not just the dangers of what might be happening physically but more concerning was what this would say about my quest to outsmart my disease and navigate my way through it all. I envisioned myself being rolled into A&E on a trolley; whispers ‘advanced cancer’; lots of well meaning pained faces; ‘tell us the event up to your legs turning blue and what other symptoms do you have’ ‘oh…so you have been to Frankfurt, arrived back today? what were you doing in Frankfurt’ (eye rolls - here we are mopping up after some foreign medical tourism disaster) - I could see the front page of the local Argus ‘woman who’s campaign we supported in mortal danger from complication from treatment in Germany’ - what about all those people who have followed my story and want to know how it goes for themselves or someone they love. I just sat in the bath staring at my legs, grunting acknowledgement in different tones to make out I was listening intently to Rupert, breath shallowing from shock, mind racing - do I call 999 now - perhaps I should rub and get some blood into the legs - stand up and gravity might help. So I stood up and began rubbing furiously. And then a very strange thing happened. The blue started coming off in my hands. And the penny dropped. This was not cyanosis or vascular insufficiency this was staining from disgusting cheap blue german (or possibly Chinese) leggings. Honestly the feeling of relief was almost worth the panic. And then the ridiculousness of the situation which has kept me going for a quite a while - making me chuckle every time I think of it.

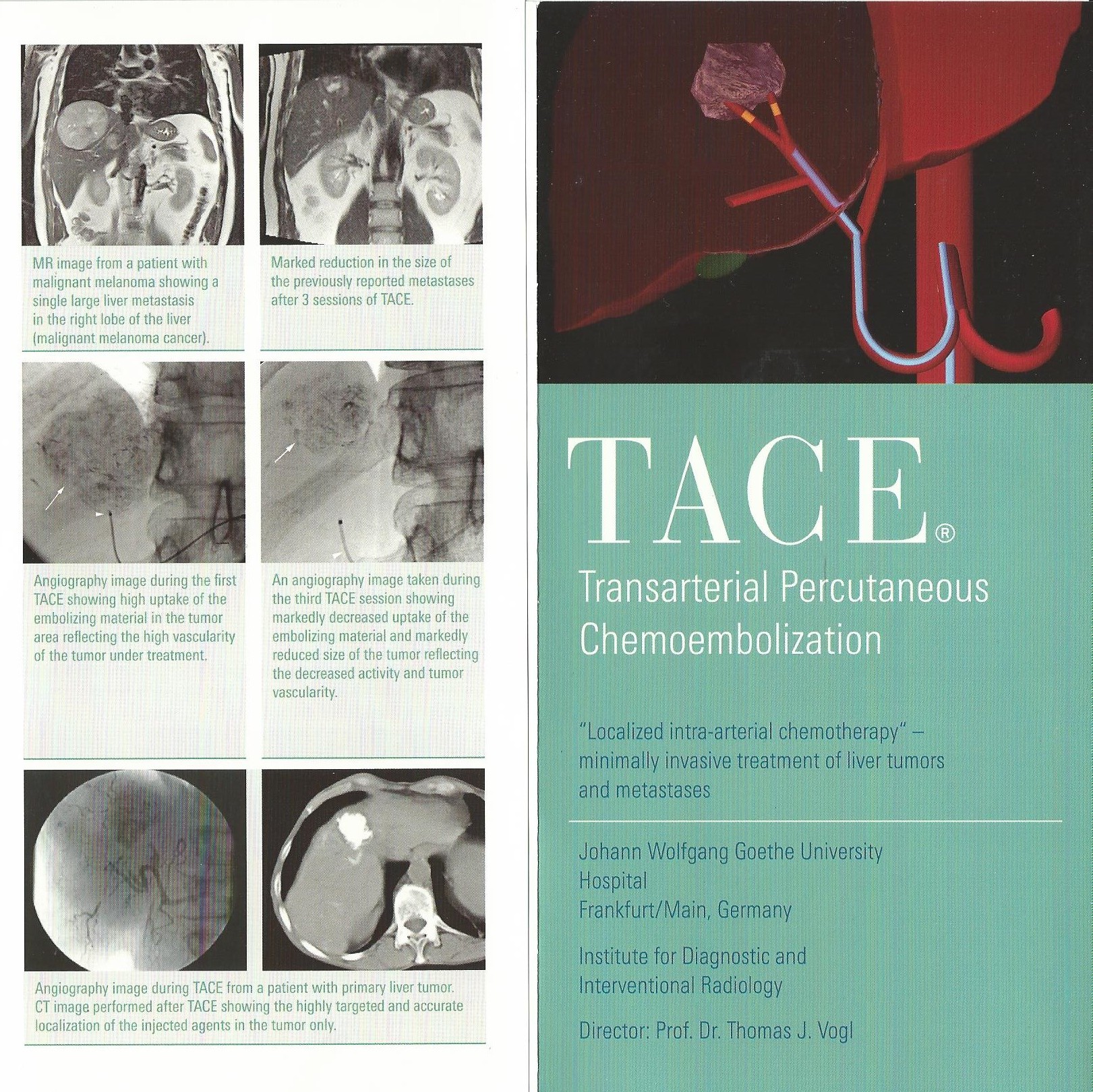

Working out what to do next withmy cancer treatment is difficult but I have discovered an amazing woman, who I mentioned before, she is Grace Gawler and has a foundation. She describes herself as a navigator. She has worked helping people with cancer navigate the many options and directions for years and is totally up to date with developments globally. She is connected with some of the most forward thinking oncologists and researchers and has helped me work out what to do given my specific situation. Unlike my oncologist, who is able to offer me only what is available and registered for use in the UK, she can identify potential therapies and advances wherever they are. This is tricky as I have to work any such care in with my oncologist who remains my primary clinician - but it puts him in a difficult situation. Prof Vogl for example simply cannot discuss each individual case with the primary provider. He assesses each patient on whether their clinical condition and treatment profile makes them eligible for treatment and in my case Grace becomes the interface. She helps filter those people who she knows would meet his criteria(I send her my bloods and other information) and then if he accepts you she will help make the first appointment. I pay for Skype sessions with her to talk through my options but also for example my supplements. She has already provided me with information which has made me change some of my supplements. I have stopped coffee enemas during the chemo treatments - as while good for helping with liver toxicity - in this case I actually want to keep the chemo in the liver to do its job. I feel so much more secure having someone with her knowledge helping me work out what to do. As she is not a provider herself she is able to share information, contacts, advise from across the spectrum knowing what my own situation is - geographically, my family, job etc - anything that makes a difference to what decisions I might make. Ultimately I am responsible but I trust her and this has made my job of working out what to do much easier. I was in danger of becoming a fantastically broad generalist with not enough specific knowledge.

I also share ideas with others I have met on line - often with broadly similar disease - and talk about what we have done and are thinking of doing and share information about treatments and advances or problems. The worldwide web really both a dangerous but also incredibly liberating place to connect and build networks impossible just a few years ago. I feel one of a tenacious group of utterly determined individuals who want to stay alive and are in search, as I am, for strategies which might help them do so. Thank goodness I did not die of some blue leg syndrome after my Vogl treatment or this would forever be on the web and deter countless people. That is the danger of the web. There is one blog about someone with advanced cancer, who was in a bad state and sought care from Vogl - it was not successful and he did die. But he also documented in painful detail the treatment and that it did not work and that he was too far gone. I don't know how many times I read this and it did deter me from seeking out Vogl independently. But Grace gave me confidence, she knows his record and he is well published. I could have been ‘British woman with terminal cancer seeks treatment in Germany anddies….Louise Howes of cancerispants fame died tragically after returning home from experimental treatment in Frankfurt this week. The treatment is not currently available in the UK for people with metastatic breast cancer. A spokesperson for the NHS warned patients to avoid being drawn in by claims of extended survival by clinicians offering care that it currently not approved for use in the UK’. But I was not - and anyway it is not experimental at all - but quite established for primary liver cancer and in some places for colorectal cancer metastasised to the liver. I am in no doubt it will not be long before it is made available to breastcancer where the disease is dominant in the liver.

My recent meeting with my oncologist was a bit awkward as he clearly, and unsurprisingly feels that it is difficult for him to safely treat me if I go elsewhere for treatment he is not responsible for. I share details of the treatment. I would really like to be choosing the route I take more collaboratively with him but know that he has to be careful and is to some extent bound by what is approved in the UK - so how can he condone treatments he is not able to refer me to. But he has been supportive. But it is a quandary. I do not believe if I rely solely on treatments available in the UK that I will stay alive as long as I hope I do by taking advantage of treatments that are more targeted that I cannot get here. I know there is a risk involved but there is equally a risk simply working through the current treatments on offer here. So - what to do. Be bold as there is quite a bit as stake - my life no less. I do have a lovely team in the UK who care for me - I think they think I am bit of a trouble maker - polite but not easy to pin down. But one of them recently kindly said ‘I don't think anyone is judging you Louise’ and that made me feel better.

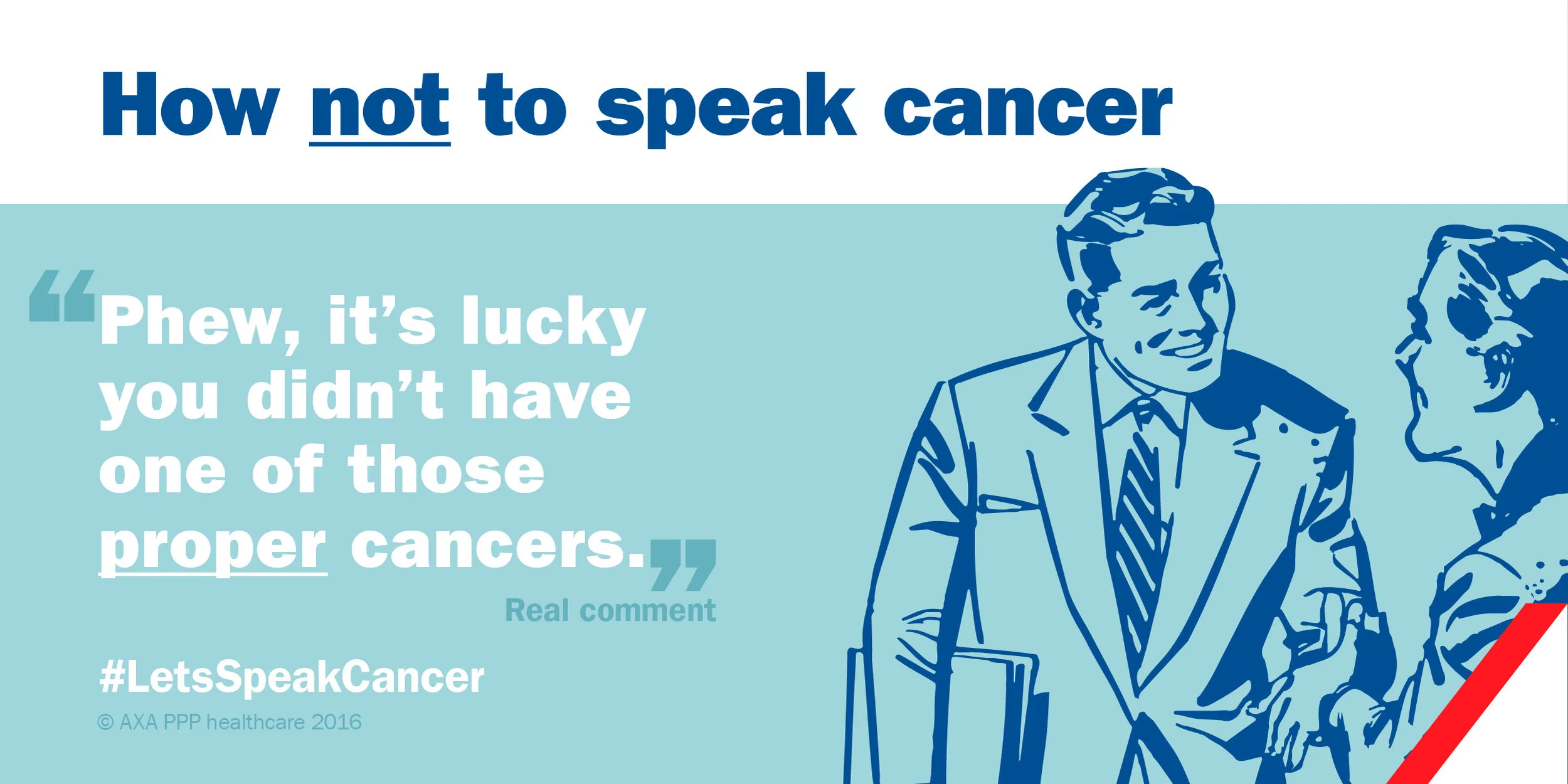

There has been a growing discussion about ‘How to talk Cancer’. There was an article in the New York Times last week and this was shared on the chat boards of Inspire (for people with advanced cancer). I was kind of surprised at the passion this discussion has prompted. I have always felt very strongly that honestly knowing what to say to someone with a cancer diagnosis is pretty hard and I therefore would absolutely not judge anyone for how they approach it, even if this means awkwardness and avoidance. It touches everyone very differently and mirrors peoples own mortality in someway, which make it doubly difficult to talk. Some people find it very easy, often you will find they have known someone close to them who have had or died from cancer and they navigate it more naturally. Others simply do not know what to say and worry that they may put their foot in it. I judge no one. Humour has always been a strategy I have used to get through difficult times and conversations - so I am the first to have rolled around laughing at comments about the savings I would make from not having to pay for hair treatments (honestly it really did save me quite a bit given I used to colour my hair relatively regularly). I don't mind if people talk about the fight or tell me stories of people who overcame it or ran marathons when they were ill etc etc. I know that these people basically want to share their love and be kind - they want to help make it better in someway and that intention is enough for me. So to judge them for the wrong choice of words achieves nothing.

The New York Times piece is about what not to say to a cancer patient. Already I do not like the subject matter. But I kept on reading. It is by a Dr Stan Goldberg a prostate cancer patient and communications specialist at San Francisco University. That says it all already. He is a communication specialist which means he is professionally committed to helping people talk about all sorts of things. So it would make sense that when he got cancer he began studying peoples responses. Goodness i would not like to have been one of those people. How to talk cancer to a communications specialist - you would absolutely put your foot in it. He provides a list of dos and don’ts - already sounds complicated. If you didn't instinctively know what to say you would have to memorise a list of dos and don’ts for fear of messing up - best perhaps to avoid the topic completely and then you definitely wouldn't say the wrong thing.

Among the don’ts were ‘preaching, unsolicited advice or recommendations, judgement and blame, uninvited discussions about prognosis, information about unproven treatmentsand your own feelings of distress’. Well I am sorry Dr Goldberg….I absolutely don't mind preaching, there maybe something useful in it; I welcome all unsolicited advice or recommendations as who knows there may be an amazing nugget in there that could make all the difference; I am not really sure what he means about judgement or blame - perhaps people wondering what may have contributed to me getting cancer - which is actually quite a sensible line of thought, it is not simply bad luck - it is the result of a series of related factors a good few of which would have something to do with my lifestyle or previous medical decisions - in my case probably using immune suppressants for 2 years, eating badly and running round juggling more than should be humanly sensible - all giving cancer a chance to take hold by weakening my immune response - if I do not consider what might have caused it how might I make changes to try and moderate its progression? Then there are uninvited discussions about prognosis. There do exist figures on average survival depending on stage of disease but these are averages and were calculated from data that are already old - so the real answer is actually who knows and I totally understand why people might want to know as it helps them respond. If the answer is that this is a cancer that is very easy to treat and almost everyone survives, that is a good thing and people can feel happy for you and hopeful, it if is that most people do not survive for many years then they are able to respond equally appropriately and be more actively helpful and present - clear about the severity of the situation.

What about ‘information about unproven treatments’ - this is a big one! What on earth constitutes an unproved treatment these days? I have come across many treatments for which there is a good level of evidence of benefit but without the standard of evidence required for it to be accepted as a mainstream treatment. A case of not enough evidence but not unproven. The outcome being these are not being made available to people who may benefit from them. Take metformin - a diabetic drug which helps restore the body’s response to naturally produced insulin and has been shown in many studies to have a protective effect in several cancers - why is this not available to advanced cancer patients? So please talk to me about any sort of treatment that may possibly help - I will then do my research and make a judgement as to the whether it is worth pursuing. And finally talking about my own feelings of distress. Why not? This is the only human thing to do - acknowledge that this must be distressing and have a discussion about it.

But this is my reaction to this list of don’ts. The discussion on Inspire simply illustrates quite how different we all are. Some people felt very strongly about how other people should or should not react and respond. So maybe some advice is useful and necessary.

A young man call Julian Quick who has a rare form of bone cancer found that some of his friends and family, and work colleagues were unwilling or unable to speak frankly to him about his condition. He was so frustrated that he started to work on a range of what he calls memes - or illustrations of awkward situations people have found themselves in with advice about how to talk cancer in such situations. He worked with AXA PPP healthcare to help come up with some do’s and don’ts. He found comments about the savings he would make from not having to use of hair products in poor taste, but I think if he spent as much money as I used to at the hair dresser he may well have found these comments less crass. We are all different but there has until now been little advice for either those of us with cancer or those of us who know someone with cancer and these resources begin to fill that gap. They are worth a read and a share.

The other side of the coin is how to talk to people if you are the one with cancer. I am not usually short of words but there are times when it is hard to know what to say, when I am not actually sure what I am feeling or thinking as these are not constants. Having to talk to people a work, strangers or even your nearest and dearest at times. AXA PPP healthcare are about to release/have just released a new guide “Let’s Speak Cancer” as well as a video guide. They are practical and give tips to those with cancer on how to talk about it. I have added the links above but also to the resource section on this site.