The strange story of my left breast

/May 17th 2015

Ned wearing my Wig- the first time round!

So Thursday was my final chemo of the 12 sessions I was prescribed back at the end of January. I have had these weekly, with a week off every third week, which stretched the course over 16 weeks. The time has passed so fast I can hardly believe this stage is now over (and pondering that time going by fast is not really what I want right now). It is almost exactly 5 years from my first diagnosis.

My wig- the first time round (Ella and I)

So I am now counted among those diagnosed with cancer who survive for more than 5 years. I think the clock starts again now. I realise there are a few factors that slightly obscure the real picture when we read about survivorship with cancer. Here are some of my thoughts. Firstly, when I read data on the percentage of women who survive five years from initial diagnosis, this figure includes those who are alive at the end of the five years but who have had a recurrence. Second, the clock starts ticking from the point at which you get your official diagnosis. So, if you have been back and forwards to your GP, referred, then hung around for tests and waited for results etc, etc then x weeks or months later you receive your diagnosis, your clock starts then. In practice you had cancer all along. This matters for me because this time round as I wonder how long I have actually had the cancer in my liver.

Making Mummy laugh!

Did I have it last summer? Last October? My diagnosis was not until the end of January – but if you are vaguely looking at average survivorship – counting from when I had that fateful ultrasound is already a good few months into actually having the cancer in the liver. So does this mean that if only x% make it after 5 years, my start point is actually further back than my formal diagnosis?

None of this thinking actually makes a difference, especially as averages are hopeless when considering individual circumstance and I am not an average and do not intend to follow and average course. But I can’t help mulling over these things sometimes, especially when I realise 16 weeks has sped by so fast.

Goodbye chemotherapy, hello Cancer Healing Action Plan! Starting with getting my strength back, focusing on my 9 strategies for healing and going to Germany. The air tickets are bought, the self-catering room reserved and my appointments with the clinic confirmed.

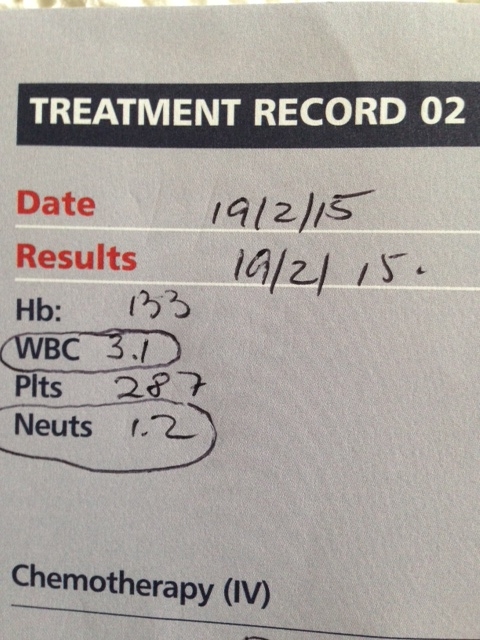

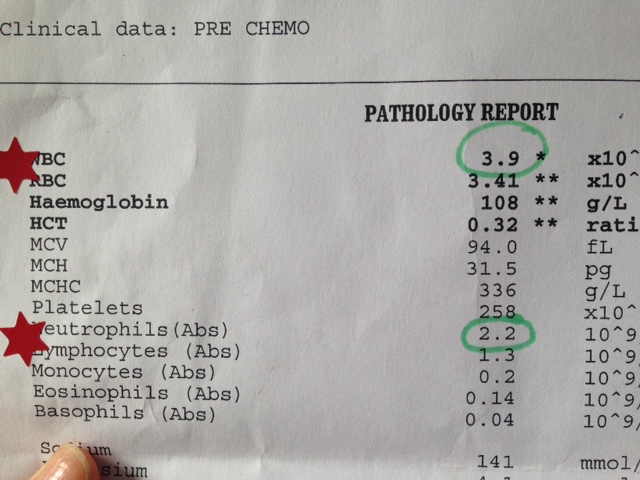

I have to share my very proud blood count moment from my last chemotherapy. Chemotherapy gives your white and red blood cells a bit of a kicking and often people need help, with a special injection, to help support their blood count. During my first chemotherapy treatment, 5 years ago, I had very low blood counts and had these injections in between treatments to help keep it up. If your bloods are not strong enough then they cannot proceed with the chemo, and this happened to me last time round, for my final chemotherapy session. I had to come back a few days later when my bloods were better. It is something that anyone having chemotherapy fears as it can mean delaying or stopping treatment. They look particularly at your white blood count, which must be above 3.0 and your neutrophil count which needs to be above 1.5 (or at least one of these two needs to be above these points).

After my first chemotherapy session (this time round) both my white cell count and neutrophils plummeted to 3.1 and 1.3 respectively (see Photo). This did not bode well given that they usually deteriorate over the course of treatment - mine did not look like they had anywhere to go. They suggested my low count indicated that, as I had previously had chemo, my bone marrow was struggling. Again not a good sign for someone with advanced cancer who may need subsequent treatments in their lifetime. My bloods remained low for the first 4 sessions over which time we were really working on the diet, the supplements and we had introduced Avemar and importantly Moxa (see earlier blog). Since then my bloods started moving upwards and on Thursday, my 12th session, they were a relatively massive 3.9 for the white cell count and 2.2 for my neutrophils. For someone at the end of their treatment, when you would normally be rock bottom, I was pretty pleased with this outcome. It just helped us believe in our ability to influence my response. Had I simply done what I did last time during chemotherapy in 2010 (ate whatever I wanted, expected to feel worse each time and let that inevitability wash over me and took not a single supplement or alternative therapy to support my body while I was on treatment), I do not believe my bloods and energy and spirit would be where they are now. It is a pity I had to be pushed to the edge to take action. Here is a photo of my bloods and my red stars from the oncology nursing team (the left one is from after my first round of chemo in early Feb and the one on the right is from last Thursday).

The strange story of my left breast

I know that I will never really know why me, and some might think it is not worth even trying to fathom this, but when it is you, you cannot help but think about it. I am not sure if this helps with the acceptance part of the process, but it does help think about how I deal with it now. Is there anything I can do now differently which may influence the course of the cancer? What about its existence is out of my control? All speculation of course, but the story of my left breast has taken up a good amount of thinking time over the years.

After my first surgery to remove the tumour

The original tumour was under my left nipple. So close in fact that while I did not have a mastectomy, I had what was called a ‘grizoti’ – a very inelegant term. An MRI showed that the tumour was too close to the nipple to preserve it, so the procedure to remove the tumour involved removing my left nipple. I still remember the day of the operation, where the surgeon, who lacked certain social skills, took out his black pen to mark me up and, talking to himself mumbled ‘hmmm doesn’t give me much to play with’, referring to the size of my breast. The end result was a nippleless, smaller breast, as they had to remove a good deal of tissue, with a pretty ugly scar over it all. Imagine coring an apple, the scar was like this, a big round, uneven circle and a vertical line down from the middle to under the breast, and a longer horizontal scar right under the breast.

I lived with it like this for almost 3 years. I could not get round to sorting out a reconstruction, and the options were quite limited in any case. Because I had had radiation I could not have an implant, and the only other way of increasing the size of the left breast, to more nearly match the right one, would involve tissue taken from another part of my body. But this was still a technique considered to have some unconfirmed risks, given the theoretical risk of transferring, or activating stem cells (not sure which) so we decided it was not an option. So what was left involved a scar revision (to sort out the ugly scar), and a slight reduction in the right breast. It took me ages to decide to go down this route as I was worried about messing up my remaining breast and maybe losing sensation. I was told that while it was a reduction, in fact it would not look like one (given my 40 year old gentle sag), it would look more like a slight uplift.

So I had the first part of this reconstruction about two years ago. The result was great, my apple core scar was transformed and my right breast looked more like that of a younger women, and both were even. Deciding on what to do with the lack of nipple took more thought. Part of me got used to not having the nipple, it was a symbol of what we had gone through, and also I wondered if I would tempt fate, go ahead and have another procedure and then have the cancer come back.

As it is, it bypassed my breast and made it to my liver, so no worries right now of more cancer surgery anytime soon to my boobs. But there was another question around the procedure of adding a nipple that also delayed my decision making. This related to the process of making the nipple. Tattooing was inevitable (these fade and you have to be retattooed over time I understand), but the big question was how to get a nipple? The option I felt the surgeon was favouring would have involved (hold your breath), cutting my other nipple in half and sewing the top half from the right onto the left. This would give me even length nipples. Hmmm. No thank you. Otherwise, if they used the other procedure – something about pulling out tissue from the breast and twisting it (I think I made that bit up), then I would have different length nipples as they would not be able to make the left one as long as the right nipple. Decisions, decisions. So I left it and never actually had that follow up procedure, but I think I was intending to do something about it at some point. Clearly not anymore – it remains a symbol of my cancer journey.

This left breast had been tricky since the age of 14. Before I get to that story I will go through some of the factors which I have considered to help me understand why me.

Genes….

I always looked very like my Grandmother (Granny), my father’s mother. I was very proud of this and enjoyed it when, walking around the village in Wales they were from, strangers would come up to me and say ‘you must be Sybil Hulton’s granddaughter – goodness aren’t you the spitting image’. Well, this resemblance perhaps came with it a stronger set of her genetic profile than other parts of my family. I lost my Granny when I was in my early 20s to breast cancer. She had first got it in her early 60s, and had a mastectomy. In those days there were no scans, no hormone tests and she had no other treatments. She did not have a reconstruction and all us grandkids knew which of Granny’s boobs was not real – I am not sure we really understood why but as young kids we whispered about it sometimes.

Her cancer returned in her early 70s, again when scanning and diagnosis technology was far behind what it is today, and she was almost yellow by the time they worked out what was going on. It was in her liver and she deteriorated quickly from when she began to have visible symptoms. She died at home with her children and grandchildren around her. I had been doing exams at university and remember racing up after they ended to say my goodbyes. I remember waking up on the morning she died and us all gathering around her bed and saying a prayer. I know it was her death from the cancer in her liver, that since my first diagnosis, has always been in the back of my mind. Anyone visited by cancer cannot help but always have a shadow of doubt every time they get a twinge or cough that goes on too long. For me, I was always scared of the liver as from my memory of it with Granny it had just snuck secretly up, and in my mind I always associated cancer in the liver with rapid and inevitable death. We are a long way from there in our knowledge, but not that far. Maybe I had a premonition – but it was always going to be the liver.

Her daughter, my father’s sister, was my lovely Aunt Jo who I wrote about in an earlier blog. She hit her 60s, having worked all her life as a nurse and eventually nurse consultant in A&E, retired only to get diagnosed with ovarian (actually peritoneal) cancer just a few months before my own diagnosis. She died last year after an incredible fight. Through this process I have had to map cancer across the family tree to determine my potential genetic predisposition and learned through this process that, in addition to a cousin who had breast cancer many years ago, and is still alive, there have been many cases of prostate cancer. In addition my Grandmother’s mother also had breast cancer in later life, had a mastectomy and died many years later of something entirely different. My Aunt was tested for the BRCA gene, but it was negative and the conclusion was that there was likely to be a genetic link but it was as yet unknown, unidentified and her blood sample is being held in a sample bank in Birmingham so that one day, as they unlock the science of genetic mutations, it may be useful.

The main difference in my case is that unlike the 3 generations before me, I did not get it in my 60s (which I thought was young), I got it first at 39. So what else might be at play? Genetic predisposition does not mean inevitable breast cancer for many people.

So I go back to when I was 14. I was at school, chatting with a group of friends in a classroom and I can’t remember what exactly made me suddenly lurch forward, but I think someone cracked a joke and I threw myself forward, hard, as in hysterical laughter, only to stab myself on the sharp corner of one of those old fashioned school desks – right in the centre of my left breast. About the most excruciatingly painful thing I have ever done, especially as at that age when everything is growing, it is very tender in the first place. This bash developed into a small cyst which I later had removed in the local hospital. I remember the shame and embarrassment of having an operation to my breast. Having to sit and have old male doctors examine me. Having my father visit me in hospital knowing he knew I had had an operation to my breast. We are not a hang it all out sort of family, bodily functions and public nudity (even within the confines of the family home) were a no no and so to have people knowing, talking about, staring at and even touching my pubescent growing left breast is even now an uncomfortable memory.

I went back to school with a great big dressing covering my chest and for weeks walked with my arms defensively in front of my chest to protect it from accidental bashes from crowded lunch queues or bustling classroom changes. I had a simple scar that went around the nipple and over time faded but was always visible.

Roll forward a few years. The next time this breast gave me gip was when breastfeeding. I got mastitis twice, badly when breastfeeding William and then Ned. Both times the left breast and both times I could feel the blockage and heat from around the same place, near and below the left nipple. A few months after ending breastfeeding with Ned I had a piece of work in Geneva at some Technical Meeting at the World Health Organisation. I was the scribe cum report writer for the meeting and so spent two full days scribbling hard as I struggled to take down notes. After the second day I felt some discomfort in my left breast and realised I had been leaning hard, pressing down on the edge of the table I was taking my notes at, almost continuously for 2 days and my breast felt warm and bruised. For anyone who has not had mastitis, it can come on very quickly and make you almost delirious as your temperature rises. I realised that my boobs had been settling down having given up breast feeding but were still slightly lumpy, and the spot that hurt was – yes, around my left nipple.

That night, in my Geneva hotel room, I could feel myself getting slightly feverish and then to my horror noticed puss coming out of the left nipple. It was late at night and I was on my own – so rang my Aunt (Jo) with her nurses hat on, and she agreed I had to go and seek help right then as if I left it till the morning I may be too ill to navigate anything myself and there was no one obvious I could turn to for help. So I put on my coat and went to the hotel reception, with my school girl French, and asked where I could find a hospital. I was directed to a woman’s hospital and took a taxi there. It was pretty deserted , except that I could hear some mothers and babies. I found my way to a reception and communicated with a mixture of bad French and actions ‘J’ai un (point to boob) et il y a un dolor, j’ai pus (puss) – il y a pus dans ma (point to boob)’. I was directed to a room where a doctor examined me and pulled out an injection – not to inject into me but to use to try and extract the pus. I was discharged with a prescription and showed a night pharmacy (I was in the Swiss part of Geneva – and I remember the course of antibiotics they prescribed costing over £100). I got myself back to my hotel room, took the pills and made my way home the next day.

As I look back I am convinced that the initial trauma was the root of all this trouble. Early calcification and ultimately an invasive tumour. I should have gone somewhere after that event, just to get it checked out, but it cleared up and I thought nothing about it. Meanwhile I suspect what might have been early non invasive ductal carcinoma – which you can cut out and be pretty confident it is all gone, crept stealthily beyond its initial location.

This is of course my own analysis of the origins of this cancer. There is some evidence that suggests an association between physical trauma and cancer (and this makes sense). Then there is some genetic propensity. And the next ingredient in my mix I suspect is the break neck speed I have lived my life. A very happy life, but goodness me have I sped along and juggled all sorts of things in a super human way. I remember at a leaving party for one job I did, my manager at the time started her goodbye speech with ‘There is one word that comes to mind when I think of Louise, and that is fast. She talks fast, walks fast, works fast’ . And everyone, including me, laughed nodding in agreement.

Rupert watched a natural world documentary once, which compared an elephant and an elephant shrew. The elephant lives many many years and the elephant shrew only 2 years. They both have the same average number of heart beats. I am clearly the elephant shrew.

I am one of a generation of girls, born around the late 60s/ early 70s who were educated to believe they could be whoever they wanted to be. Professionally the world was a place where women finally had opportunities and could have aspirations that had simply not been available to their mother’s generations. I worked so hard, I was going to be one of these women and really I succeeded. In my professional life I ended up working in a career I have been devoted to since my late teens, working in international health and development, but the process of getting there was incredibly hard. Theoretically having opportunities to be who you want to be does not really stack up with the realities of family life. No one said that childcare and your ability to pay for this, balance the demands of home and work would be one of the most significant challenges to women progressing in a professional capacity. I had Ella early, so was a mother relatively young (25) and spent my early professional life juggling not just one baby but 4. My husband had a job which took him away frequently so I managed the logistics of job, childcare and homelife – and yes it was often absolutely punishing, I frequently felt triumphant that I was managing it. The trouble with juggling so much is that it takes very little for the whole house of cards to come tumbling down, an ill child on the day of a major presentation at work, a call from school because your child has been concussed in a playground accident.

My First WIG

I worked initially in Brighton while they were very young (Ella was 6 when Ned was born, at this time I had 4 under that age), I balanced a full time job while studying for a Phd, which took me 5 years to complete but I did so while childbearing, sleepless nights, exhaustion. Then when Ned was 2, with my Phd complete, I started with my current company with whom I have been ever since. This involves lots of travel oversees as I lead and managed work in Nepal, Cambodia, and more recently across Africa including Northern Nigeria and Sierra Leone. Having to coordinate travel with Rupert so that there is always one of us at home, has involved super human coordination skills and every time I go somewhere the task of developing the family timetable, in intricate detail (to avoid a child being left with no lift home, a trumpet exam missed or a non uniform day forgotten) devoured many of my waking spare hours.

I would not change my past, but I am certain that the breakneck speed with which I have lived it, and packed so much in has contributed to creating an environment within which this cancer has taken advantage. I have probably seen more friends in the last 16 weeks than I saw in any one year over the past 18. Simply not commuting to London, as I have been working mainly from home over this time, and not getting on an aeroplane somewhere has bought me hours in the day and given me space to just be with the kids a bit more. They were used to our frenetic lifestyle and as long as one of us was at home they were settled, but it has not been without its costs. Every mother I know beats themselves up about their work life balance and I have done my fair share of this over the years. I look at my gorgeous kids and how settled they are and I do not regret except perhaps reflect that maybe I should have just spread this all out over a longer time-frame, why did I need to go quite so fast.

But I am where I am. Maybe this has had nothing to do with the cancer, but I do feel like an elephant shrew. I have had a full, full happy life which I have lived and used up a fair share of my heart beats. So I am slowing it down a bit now to stretch those last ones as far as I possibly can.

Meanwhile…next on my treatment journey is the end of chemo scan. SCANXIETY sets in. My liver blood markers have all been within normal range over the last 2-3 chemos. One – GGT – which is an indicator of liver damage was 148 when I started, it is now 33. Normal range for this is 0-40 – so it is near the high end of normal range but still it has reduced. Surely this means the cancer has retreated. But if so, by how much? My liver continues to gripe, which I see as pain from cancer cell death – inflammation and the death throes of the cancer cells, but even so the fact I can feel it disturbs me. There must still be enough there to still be dying. I would like to think it was pretty much blitzed. And so the thoughts go on, round and round. What I do know is that it I need to be patient. That stable is OK. That even if you cannot see cancer it is still there and that any solution will require time and will involve focus on my cancer action plan over a much longer time scale. The scan is on the 21st and I get the results on 26th.